2019-04-05 08:00:00

Attracting more developers to F#

UPDATE: If you are reading this piece, please also read the follow up post I published a few days later.

Sometimes folks complain about Microsoft's posture toward F#.

You've probably seen these kinds of remarks on Twitter and GitHub and so on. People compare the amount of attention and resources that Microsoft gives to F# compared to C#. Terms like "second class citizen" and "red-headed stepchild" get used.

In some cases these comments are accompanied by strong emotions, expressed either directly or with sarcasm.

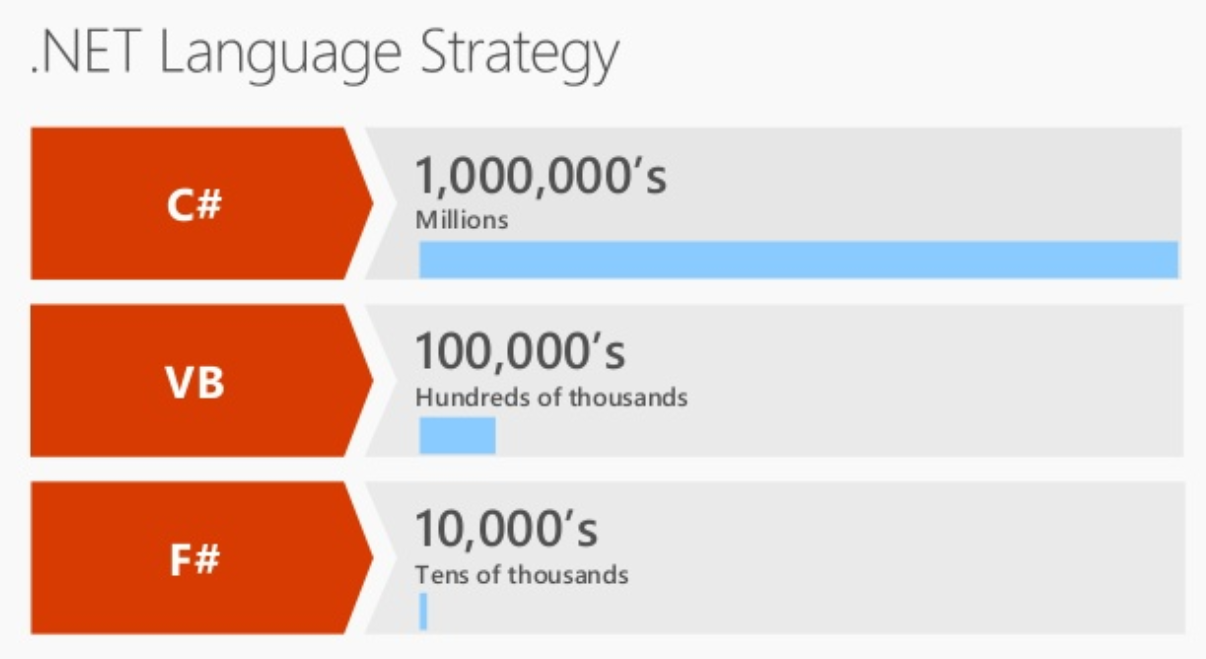

Let's acknowledge that Microsoft DOES give more attention to C#, and for good reasons. The following picture appeared in one of the slides during a presentation at Build in 2017:

C# users outnumber F# users by two orders of magnitude. That's huge. Giving a lot of attention to C# just makes sense. It's all about the users.

So the real question is...

Why don't more people use F#?

This post is a follow-up to another blog entry I wrote back in 2015. The nutshell summary of that piece is that F# is a "discontinuous innovation", so Geoffrey Moore's chasm principle applies, which means that F# will never take over the .NET world, because C# is simply too good.

So, four years later, where are we? It looks to me like F# is continuing to grow, and a lot of good F# things are happening. But in the big picture, some things are basically unchanged: C# is still FAR more widely used. F# is still considered esoteric.

Here's an example of how this plays out: In the recent election for the .NET Foundation board, AFAICT, none of the winning candidates identify as an F# developer, and only one of them even mentioned F# in their candidate statement. Please understand that I'm not saying this as a complaint. This is merely an interesting barometer reading of where we are. In other words, with respect to F#, the election result is an accurate reflection of the .NET ecosystem, because there are only six board slots, and F# is used by far fewer than one-sixth of .NET developers.

So, if we want more people to use F#, what do we do? Is the situation hopeless? I think not. But with all due respect, complaining about Microsoft's resource allocation won't help.

My claim is that we (F# fans) need to examine how we are contributing to the problem.

F# Positioning

First let's talk about the different ways that we can view F# and its place in the world. As is my tendency, I will speak of this as an east/west continuum with two endpoints.

F# is:

| An ML dialect that happens to run on the CLR | ---------------------------------------- | A .NET language that happens to be an ML dialect |

The "west" endpoint (to the left) is about perceiving F# as primarily a functional programming language. The fact that F# runs on .NET is merely an implementation detail. When we develop with F#, we are usually not thinking about .NET.

To the "east", at the other end of the spectrum, we speak of F# as primarily a .NET language. The fact that F# runs on .NET is important. When we develop with F#, we are often thinking about broader aspects of .NET.

Let me first say that both of these perspectives (and all the shades of gray in between) are valid. I'm not here to tell you how you must view F#.

However...

Here's what is NOT going to happen

If your perspective of F# is near the west end of my continuum, I assume that you are NOT one of the people who is upset about Microsoft's level of attention for F#. And if you are, I further assume you believe that shouting at the rain will make it stop.

Seriously. This isn't gonna happen. Microsoft is not going to try to convert the world to the functional programming paradigm.

To be clear, I should explicitly say here that I don't work for Microsoft and do not speak for them. My remarks here should be seen for what they are, opinions and predictions from an outsider.

Still, this should be obvious. Microsoft is all about .NET.

Back to the point...

A specific example

In late 2017, issue #3976 was logged in the GitHub repo where the F# compiler is developed.

Nutshell summary: The F# compiler has its own backend (which, like the rest of the F# compiler, is written in F#). Somebody suggested replacing that backend with System.Reflection.Metadata, which is what the Roslyn compiler uses. Don Syme said no. The issue was closed.

Let's think for a moment what it might mean for the F# compiler to share a backend with Roslyn. It seems likely that such a move could greatly affect the way people inside Microsoft think about F#. Maybe folks in DevDiv think of F# as "separate", and moving its compiler onto Roslyn's backend would help change that. Maybe the increased interdependence between F# and the rest of .NET would make it more fully recognized as an important part of the .NET story.

In short, I believe a shared infrastructure for the F# and C# compilers would move us at least somewhat eastward.

So am I saying that Don Syme made the wrong choice? Certainly not.

But I do wonder how often that same decision pattern gets applied in other contexts.

Simply put, the compiler is a special case. It is essentially always a good idea to have the primary compiler for a programming language be written in that language.

But what happens if we take this sort of "F# only" mentality and apply it to all kinds of other libraries and projects? Broadly speaking, that philosophy adds westward pressure.

And like I said, there's nothing inherently wrong with the west side of my continuum. Functional programming is cool.

But if we want to promote more adoption of F#, the solution lies to the east.

Painful transitions

So all that stuff I wrote about F# and the chasm? It wouldn't be quite as applicable if it were possible to adopt F# more incrementally.

Technologies that can be adopted gradually don't really have chasm problems. The chasm exists for "discontinuous innovations", where the change causes a lot of pain. I'm talking about situations where you can't really adopt The New Thing unless you give up the way you do things now. That's what creates the chasm.

And that's why most people don't use F#. It's just too big of a change to swallow.

Things might be different if F# had features which are conceptually familiar to C# developers. Like, you know, if F# had support for classes and mutable variables and loops and object oriented programming -- that would be cool.

Things might be different if F# could interoperate with the rest of the .NET world. Like, you know, if it were possible to have an app which is written partly in C# and partly in F# -- that would make things so much easier.

Okay, I'll stop the silliness. Yes, I know that F# already has these things. I'm trying to make my point by pretending otherwise.

Seriously. Imagine trying to put together a credible story for how to make a gradual, incremental, pain-free transition from C# to Haskell.

No, really. Try to imagine that. I'll wait.

In contrast, the corresponding story for F# basically writes itself. If you want to get started with F#, you can have some working F# code in your repo by the end of the day. Your solution might have 50,000 lines of C# code, and none of that has to change when you add 50 lines of F#.

So why does the F# chasm exist?

Because we created it.

Or at the very least, we make the chasm wider.

F# has all kinds of stuff to support a great story about very incremental adoption, but that is not typically what we emphasize when we're talking to someone. Instead, we seem to think the way to get people to switch to F# is to explain how it's "better". Here's why that doesn't work.

When we say this:

The F# type system IS just so much BETTER, with discriminated unions AND records, the functional paradigm is really POWERFUL.

What people hear is this:

___ F# ____ ______ IS ____ __ ____ DIFFERENT, ____ _____________ ______ AND _______, ___ __________ ________ __ ______ SCARY.

Every time you say "better", people hear "different". That's just the way it is.

Talking about how F# is better than C# is usually self-defeating. Because if F# is really that much better, then it must be really different, which probably means the change is going to be painful or expensive.

Promoting incremental adoption of F#

If you actually WANT to evangelize pure functional programming (on .NET or anywhere else), ignore this article and go back to measuring your chasm. It's wide.

But promoting F# can be much more effective than that, if we emphasize incremental change. In fact, even the word "change" isn't quite right, as the choice to use F# can be purely additive.

One thing we need to do is celebrate all parts of F#, not just the parts that are associated with the functional paradigm.

Sometimes we talk about F# kinda like this:

Yeah, F# is a multi-paradigm language, but it's really supposed to be used for functional programming. Real F# is about is functional purity. There are various escape hatches available, such as classes and mutable, but we should feel shame when we use them.

This kind of messaging is NOT the way to help F# people understand that F# can be adopted gradually.

It's also not necessary. Yes, there are some great benefits to be had in functional programming, but trying to start people at the west endpoint is what creates the chasm and drives people away. The goal of promoting F# adoption should be to get people who are OFF the continuum to relocate and be ON the continuum, and the easiest point of entry is the east endpoint, using familiar things like classes and objects and mutable collections.

And by the way, there's no need to worry that they might stay there and never experience functional programming in its full glory.

First of all, even if they did stay east, would that really be a problem? F# is a pretty great language for OOP. If they like using it that way, why not let them be happy?

Second, they won't stay there. Once someone gets on the continuum, it's hard to stay at the east endpoint with the wind constantly blowing to the west. Most people will find a comfortable spot somewhere in the middle.

THIS is what makes F# a great language.

You don't have to take my word for it

The F# repo on GitHub contains, among other things, the source code for the compiler I mentioned above. Running git log shows over 6,800 commits, around 20% of which were done by Don Syme himself.

So what kind of F# code does our BDFL write?

A quick grep shows that mutable is used 246 times, and that's just in the backend. Casual browsing through the code shows plenty of classes. I even found places where they use regular mutable collections from System.Collections.Generic.

And we should not be surprised. If Dr. Syme didn't want these kinds of features to be used, why would he make them part of the language?

Bottom line

The least effective way to promote F# adoption is the one that comes most naturally, a narrative that includes criticism of C# as part of our claim that F# is better.

Instead, we need an entirely different and more positive narrative: ".NET development with C# is great, and adding F# can make it even better."