2009-02-16 17:51:06

Git is the C of Version Control Tools

I've been working lately on a major revision of Source Control HOWTO. The plan is to publish an expanded version of this material as a book later this year.

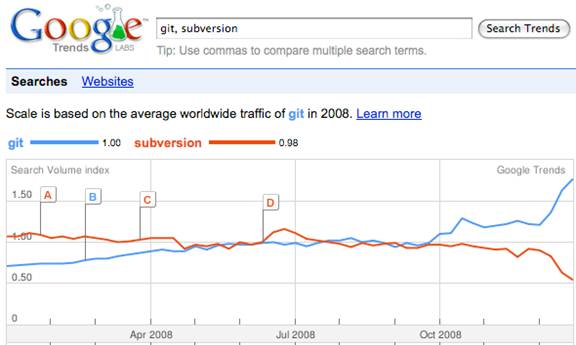

The original series of chapters was written almost five years ago, and the content is looking rather dated here in 2009. One of the biggest problems is that no book on this topic can be truly credible these days without covering distributed version control tools like Git and Mercurial. These tools aren't mainstream yet, but their popularity is growing very fast.

So as I overhaul the content for book publication, I am including lots of new stuff on distributed version control and how it's different.

And that means I am spending a fair amount of time using Bazaar and Git and Darcs and their ilk. Broadly speaking, I think these tools are fascinating.

But I keep stumbling across little things that surprise me.

git add -p

Some folks say that Git's killer feature is its index. That's like saying that C's killer feature is the ability to cast an int to a pointer.

Git's index is neato, but it allows you to do things that may be unsafe. At first I didn't get this. Whenever I was reading about the index, I thought it was equivalent to a pending changeset, a simple list of changes in the working copy that are waiting to be committed to the repo.

But Git's index isn't just metadata. It doesn't just point to things in the working copy. It actually contains its own copies of things.

And this is where Git's index is both cool and not cool. One of the best practices I suggest in Source Control HOWTO is to never use a version control feature which encourages you to checkin code which you have never been allowed to compile and test. This is exactly what Git's index allows the developer to do.

- By using "git add --p", you can choose which patches from a file you want to include for checkin.

- The result is that the index contains a version of the file which is not in your working copy.

- If you fire up your build tool, it will compile the version of the file that is sitting in your working copy, not the one tucked away in Git's index.

- If you run your unit tests, they are not testing the contents of the file that are about to be committed.

- So when you type "git commit", your repository will contain something that has never been compiled or tested.

- This is not a Best Practice.

That doesn't mean Git or its index are bad. I'll agree that "git add --p" is a very powerful feature that has its place. But in this respect, Git is a bit like C.

- C is fast, hard-to-learn and it allows the developer to do things that are probably a bad idea.

- Git could be described in exactly the same way.

Not that there's anything wrong with that. :-) I could actually see myself using "git add --p", but that doesn't mean it would be a smart thing to do.

And I would adopt the same mindset I use when I'm coding in C. Whether you're using C or Git or a 12-gauge shotgun, you need to act differently than you do when you're in an environment that attempts to protect you from your own mistakes.