2009-03-16 13:00:00

DVCS and Bug Tracking

In last week's entry, I mentioned my

interest in Fossil, a relatively new

DVCS written by the author of SQLite. In the comments on that entry, a guy

named Benjamin Pollack picked a fight with

me about why I think Fossil is interesting.

In last week's entry, I mentioned my

interest in Fossil, a relatively new

DVCS written by the author of SQLite. In the comments on that entry, a guy

named Benjamin Pollack picked a fight with

me about why I think Fossil is interesting.

It turns out that this guy is actually one of Joel's minions over at Fog Creek. In fact, he joined the company as one of the interns on Project Aardvark back in 2005.

To Benjamin, I would like to say that "interesting != good". Some things are interesting in spite of the fact that they are crap. And some things are interesting BECAUSE of the fact that they're crap.

And to D. Richard Hipp, the author of Fossil, I would like to say that I am not saying Fossil is crap. In fact, I am currently taking no position on whether Fossil is good or bad. For now, I just think it's interesting, mostly because I think the issues of DVCS integration with the rest of the ALM tool suite are important.

But before I talk more about that, I can't resist offering a few remarks about Fossil itself.

Comments about Fossil

- Benjamin Pollack complained that Fossil handles merge

conflicts poorly. And he's right. When it inserts markers around the

conflicting text, it should clearly indicate what came from which file.

- Why does each instance of the repo have its own list of

users? I would have expected that this information would sync during a

push/pull operation.

- The 'fossil ui' command is conceptually cool. It runs a

built-in web server and launches a browser pointing at it, providing a

web-based way to interact with all the features of Fossil. But Fossil's

web UI isn't going to win any awards for aesthetics. It's 2009, and the

world is getting less tolerant of ugly things in web browsers every year.

At some point, making Fossil pretty would probably be worthwhile.

- Fossil is really easy to configure. It's just one executable file. And setting it up as a server is simple, either using its built-in server, or running as a CGI, or running through inetd. Very nice.

Distributed Bug-Tracking

Industry-wide, there is a trend toward more integration between version control and other stuff like project tracking, wikis, discussion forums, build tracking, etc. Developers don't just checkin code. They use a whole bunch of other tools which help them collaborate with each other and with people in other functional areas.

While DVCS is one of the more interesting things happening right now, it does represent a setback in this particular area. The benefits of a DVCS are somewhat diminished if all of the other tools a developer needs are still "centralized".

Yes, it's cool that I can commit my code while I'm on a plane, but how do I update the FogBugz case to mark it fixed? So far, the answer is that I have to wait until the plane lands, hope the airport has Wi-Fi, login to my corporate VPN, bring up a web browser, remember the case ID, find the case, change its status, and try to remember my code changes so I can write something relevant in the comments.

As long as this is the answer, then I assert that the story for DVCS is, well, incomplete.

Other relevant projects

As far as I know, Fossil is the only tool which is a DVCS with bug tracking built-in. But it is not the only project exploring this area of need. Others include:

I have spent some time looking at each of these, but not enough to make detailed comments. Let's just say that I consider all of them interesting in the same way that I think Fossil is interesting.

Things I think I think

After looking at everything I can find in the area of distributed bug-tracking, I found myself with more questions than answers. But I am starting to collect some things that I think are correct. I think.

I think bugs deserve their own DAG.

I think everybody's first thought about bug-tracking with DVCS is that the bugs should be stored in the version control tree as text files that can be merged. Whenever the tree branches, the bugs will automatically branch as well. A bug can be marked as fixed in the branch where it is fixed.

But the more I think about this design, the more I think it would cause a lot of regrets later. I think bug tracking records probably need their own place, living in their own DAG. There are just too many scenarios where the bug-tracking info is being updated without changing anything in the tree.

For example, consider the QA team. When they update a bug to mark it as "fix verified", you don't really want them doing this operation as a commit to the version control tree, do you? In fact, you probably want the bug-tracking and version control areas to be controlled by a completely different set of access permissions.

Fossil got this right, sort of. Tickets are separate from the tree.

But Fossil's design isn't perfect. Tickets are actually not managed with a DAG at all. Rather, the algorithm for resolving conflicting changes is something like "the version with the latest timestamp wins". Do we credit the author for not over-designing? After all, this guy did SQLite, so he knows a thing or two about how to implement "just enough to be incredibly useful". Or is this design likely to make users really angry when it causes an unpleasant surprise?

I think bugs deserve their own merge algorithm

Once again, the first thought here is probably not the right one.

A DVCS knows how to deal with merging changes to text files. So if we want to store bugs, then obviously we should keep them in text files so we can re-use all that merge code, right?

I don't think so.

Stuff in a database is very highly structured. We have lots of information which can be used to implement really good merging. In theory, merging changes to a bug-tracking database should work much better than merging changes to code.

(Yes, code is very highly structured as well, but the only way to get that information is to parse the code. I've seen some interesting research in the area of language-specific version control tools that manage code changes with a parse tree representation, but I don't think those things will be practical mainstream solutions anytime soon.)

Anyway, if you take a bug record and throw it in a text file and then use regular old file merge to resolve changes, it seems like you're throwing away a lot of the information you could be using.

Admittedly, writing a special merge algorithm for this case would be a TON of work. But the results might be worth it. It might be the difference between a distributed bug-tracking system that constantly annoys its users and one that Just Works.

I think bugs deserve their own sync patterns.

The use cases for distributed bug tracking are different than distributed version control.

For example, it seems very likely that we want to sync our local instance of the bug-tracking database a lot more frequently than we want to sync our local instance of the version control tree.

If I've got a live connection to the central server, then I want to be pulling down updates to the bug db all the time.

If I add a comment to a bug, I probably want that comment pushed up to the central server as soon as my network connectivity allows.

With version control, I want a private sandbox so I can work on a bunch of code changes and only push them up to the central server when I'm done fiddling with them. That kind of workflow strikes me as far less important for a bug-tracking application.

I think distributed version control needs distributed bug-tracking

I've just explained several ways that distributed bug tracking needs to be different from the way a DVCS works. But I still think that pairing a DVCS with a centralized bug-tracking solution makes very little sense.

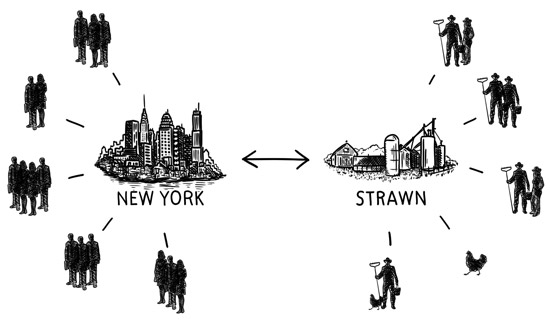

Consider the scenario where a company is doing development in two cities and wants each of them to have their own server.

We actually get this request quite a bit from Vault customers. Somebody calls and says they have a team in New York City and another team in Strawn. They want each team to be doing work on their own central server. And they want the two central servers to synchronize with each other at some regular interval.

These people are asking for a DVCS. They don't care about the "coding on a plane scenario". They don't really care so much about private workspaces or the performance benefits of having the entire repository on every developer's machine. They still want a central server. The only difference is that they want TWO central servers. And a DVCS can do that.

And if they are using more than just version control, then what they really want is for ALL developer-related stuff to follow that same workflow. Every four hours when the two central servers do their sync-up, a bunch of changesets get pushed in each direction. Some of those changes are modifications to the version control tree. Others contain changes to the work items or the wiki pages or whatever.

I think DVCS will stay small until it becomes a "whole product".

My regular readers know that I am a fan of Geoffrey Moore's classic book, Crossing the Chasm. One of the ideas in that book is that new innovations don't go mainstream until they become a "whole product". Right now, most of the comments about DVCS that I am hearing out in the industry are negative.

Some of them are saying that "DVCS will never be mainstream". More and more, I think those people are wrong.

Others are saying that "this DVCS stuff just isn't ready yet". Right now, those people are right. For a large portion of the market, version control alone is not a complete solution. They want the whole product, and they want it to work together seamlessly.

If DVCS wants to reach that part of the market, it needs to figure out what "distributed" means for bug-tracking and wiki and forums and change management and build tracking and test management and requirements.

I think Benjamin Pollack is an irritating kid who quibbles too much.

Or rather, I did until I saw his bitbucket page. Anybody who writes a C implementation of an AVL tree FOR FUN has my complete respect. :-)